- Ιατρείο

- Συμπίεση Αγγείων

- Έχετε απορίες;

- Λόρδωση – Αιτία για πολλά σύνδρομα συμπίεσης στην κοιλιακή χώρα

- Το Σύνδρομο «May-Thurner» Σύνδρομο «May-Thurner»/ Σύνδρομα «Cockett’s»/ Σύνδρομο Συμπίεσης «Vena iliaca»

- Σύνδρομο Μέσης Γραμμής (Σύνδρομο Συμφόρησης Μέσης Γραμμής)

- Σύνδρομο Πυελικής Συμφόρησης (Συμφόρηση των Οργάνων της Λεκάνης)

- Συμπίεση της Κοιλιακής Αρτηρίας/ Σύνδρομο Dunbar/MALS/ Σύνδρομο Ligamentum Αrcuatum

- Σύνδρομο Wilkie / Σύνδρομο της Άνω Μεσεντερίου Αρτηρίας (Arteria Mesenterica Superior)

- Pudendal νευραλγία σε σύνδρομα αγγειακής συμπίεσης

- Θεραπεία συνδρόμων αγγειακής συμπίεσης

- Πρόσφατα ανακαλυφθέντα σύνδρομα αγγειακής συμπίεσης

- Η Διαγνωστική με Υπερήχους

- Η Μέτρηση της Ροής του Αίματος – Η Μέθοδος «PixelFlux»

- Προσόντα και Πείρα

- Ιός «Borna Virus»

- Επιστημονική συνεργασία

- Cookie Policy

- Cookie Policy (EU)

Pudendal νευραλγία σε σύνδρομα αγγειακής συμπίεσης

Pudendal neuralgia is the medical term for pain in the territory of the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve is running from the spine towards the sacral bone and then curves anteriorly towards the region around the anus, the vulva, encompassing the orifice of the vagina and the urethra as well as the clitoris, the major and minor labia, and the scrotum/penis respectively.

Pain in this region is causing substantial discomfort and a deterioration of the quality of life. Pudendal neuralgia interferes with basic biologic functions as micturition, defecation, sexual intercourse and affects the ability to sit or stand or move around ot to stay put in certain body postures.

Thus, it constitutes a severe medical condition. Unfortunately, its treatment is not fairly straightforward since the diagnostics of pudendal neuralgia is not an easy one.

The causes of pudendal neuralgia may be many and may be related to different anatomical structures, different functional influences onto the nerve and may thus require a differentiated therapeutical approach.

Here, a list of free available medical papers can be downloaded.

Not well known is the fact, that vascular compression syndromes may cause pudendal neuralgia.

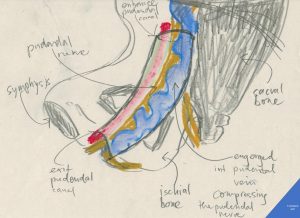

Author’s schematic drawing of the pudendal nerve compressed inside the pudendal (Alcock’s) canal by an engorged internal pudendal vein as it happens in pelvic congestion syndrome

The pudendal canal (Alcock’s canal) is a fibrous tube running along the medial surface of the ischial bone (the green nerve in this illustration). It contains three important structures:

1. the pudendal nerve – serving the perineal area, the anus, the major labia (scrotum) , clitoris (penis), the orifice of the urethra, the vagina by mainly transmitting sensory signals (pain)

2. the internal pudendal artery – a comparatively hard structure (due to it’s muscular wall and the arterial pressure inside)

3. the internal pudendal vein- a comaratively soft structure (due to it’s thin fibrous wall)

Under normal conditions all three structures find their place without pressing against their neighbours.

In pelvic congestion, however, the soft walled pudendal vein suffers an ever increasing pressure since the blood cannot leave the pelvis (due to a May-Thurner constellation or rerouting of renal blood when the left renal vein is compressed – aka Nutcracker-syndrome). Then the pudendal vein enlarges more and more and even starts meandering inside this narrow canal.

Then after a while the growing lateral bulging buds of the meandering vessel press tightly against the nerve. The nerve does what it alwayas does when it receives a signal – it transfers sensations to the patient’s brain. But now those sensations, felt as if coming from the nerve’s perineal periphery, are not short and easy ones as if the area had been lightly touched. They grow to unbearable burning and stabbing chronic pain rendering live barely bearable – the full-blown clinical picture of pudendal neuralgia.

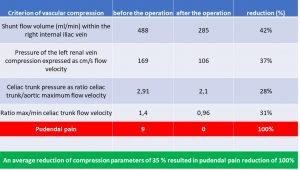

The table to below highlights some relevant criteria of multiple vascular compression syndromes ( namely MALS, left renal vein compression and May-Thurner syndrome) in a patient of us with severe and disabling pudendal neuralgia which was operated to reduce some of the vascular compression. This resulted in 100% relief of pudendal pain

The pudendal pain reduction is referred to a decrease of pressure in the congested pelvic veins. This elevated venous pressure inside the wider pelvis is also transferred to the vein within the Alcock canal which runs parallel to the pudendal nerve in this tight tubular cavity at the inner surface of the ischial bone.

Illustrated cases of patientes duffering from pudendal neuralgia

1: female patient 34 yrs

The patient was suffering from progressive dilatation of veins of the entire right leg and gradually increasing pain in this region. Some of the most dilated veins had been stripped and the external pudendal vein (which runs at the medial circumference of the upper thigh) was embolized.

After her second pregnancy the varicose veins reoccurred and became painful as never before. The leg felt very heavy.

Then, in a second embolization, numerous pelvic veins were occluded which was answered by even more severe pain in the right leg. After this procedure, one year ago, also the left leg became painful and heavy. Moreover, the pain extended now to her buttocks and genitals – these are the symptoms of a pudendal neuralgia. Now the decision was made to remove some of the embolization-coils. Again – without any effect on her pain which even further extended to her lower back. The patient lost altogether 6 kg in this time.

She undenlvent a laparoscopic left salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the ovarian tube and the ovary) some months ago and unfortunately, continued to suffer with quite debilitating left iliac fossa pain (pain in the lef tlower abdomen). This was compounded by the fact that her right leg has seen a profuse proliferation of varicose veins.

At the time of our functional color Doppler sonography with PixelFlux-measurements she was suffering from severe flank pain and back pain, mainly on her left side, a severe lower abdominal pain, bulging veins in the left groin and in the genitals, inability to walk and sit for longer times, severe nausea which started about 2 minutes after a meal, and vomiting in the morning.

My actual ultrasound findings were:

The patient was suffering fom multiple vascular compressions:

- MALS

- May-Thurner-Syndrome

- Lordogenetic left renal vein compression (aka Nutrcracker-syndrome)

- Bilateral femoral vein compression

- Pelvic congestion

- Vena cava inferior compression

All but one (1 /MALS) directly contributed to her leg varicosis and pelvic and genital pain. MALS was responsibel for her nausea, weight loss and vomiting. The attempts to reduce the leg varicosis by embolization could not be successful since it was not taken into consideration by the interventionalist that this severe and relapsing varicosis must have had a reason which had to be sought in the higher (more cranial) venous vessels. Their obstruction did not allow a normal drainage of blood from the more caudal veins in the legs and in the buttocks as well as in the genitals. The patient’s veins literally filled up like a reservoir which receives more fluid than is taken out. Comparable to a rain barrel the deepest lying veins dilated first (in the leg) and then, after their capacity was exhausted under increasing pain, higher venous territories were flooded and became varicose and painful as well: genital veins (internal pudendal vein), the lower abdomen (iliac veins), the buttocks and lower back (gluteal and spinal veins).

The repeated embolization and the ovariectomy (removal of the left ovary) plus the coiling of the left ovarian vein increased the problem further. These procedures were undertaken under the assumption that the reduction of the venous pressure inside the varicose veins would reduce the pain in these veins.

This very widespread concept is basically wrong, if an outflow obstruction in more cranial veins exists. Then such procedures reduce the venous capacities but do not improve the venous return to the heart. Thus, exactly the same amount of blood as before the embolization is now forced to run through even thinner veins – the larger ones which before took more blood just have been removed by the interventionalist. The logical and unavoidable consequence is the emergence of new varicose veins and more pain. The pain is increasing since it is generated by an inflammation of the venous wall. This inflammation is triggered as a repair process when shear stress disrupts microfibers of the connective tissue mesh which supports the wall of the veins. So, the pain is proportional to the degree of inflammatory repair which produces cytokines and prostaglandin-derivates. These molecules elicit pain in the venous wall. Any increase of venous pressure above the stretchability of the connective tissue mesh will inevitably produce pain.

If now the large veins are removed, smaller veins must take over the same amount of blood which already caused too much shear stress for these larger veins. The shear stress in the remaining smaller veins will soon exceed the values on the recently removed veins.

The only and logical consequence is: more pain after such interventions!

That is why a fundamental different approach must be followed:

The entire venous network of the patient needs to be scanned with a quantitative functional color Doppler examination. Only the exact measurement of the blood volumes and their pressure and their flow direction and their bypasses and their functional effects can guide a knowledgeable vascular surgeon to the necessary steps. These aim at a reconstruction of the undisturbed venous return to the heart.

Such an operation was carried out and led to a fast improvement of the patient’s pain.

Here are some relevant sonographic findings. They underscore the need for a complete and functional examination of all relevant vessels. This cannot be done in a few minutes nor in a conventional workflow. An experienced physician with the necessary theoretical knowledge and the ability to depict all relevant structures in good imaging quality is required as is a high-end ultrasound equipment with cutting edge transducer and measurement software.

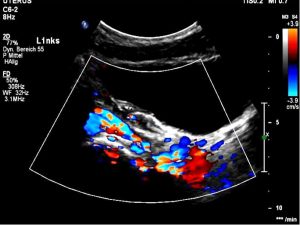

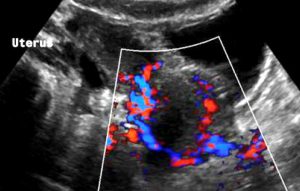

Severe pelvic congestion with enlarged veins filling up the uterus’ muscle layer (myometrium) with sponge – like venous collateral veins

Extreme left renal vein compression – no blood at all passes the aorto-mesenteric clamp. 1- aorta; 2 – superior mesenteric artery; 3 -splenic vein – also compressed; 4 -congested and dilated left renal vein (black: no flow) left to the aorta; 5 – compressed segment of the left renal vein – also without blood flow, thus appering without coloration

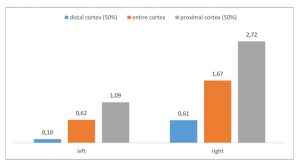

The PixelFlux-measurement of the renal perfusion [cm/s*cm²/cm²] is the only technique to quantify the true functional impact of the left renal vein compression. Here it shows the extreme suppression of the parenchymal perfusion of the left kidney as a sign of the severity of its compression on the one hand and as a sign of the lacking collateral relief on the other hand

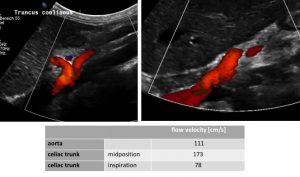

MALS: compressed celiac trunk , wrapping around the median arcuate ligament (left image) – decompressed celiac trunk in inspiration – running now in a straight fashion (right image) and flow velocity measurements of the relevant vessels (table)

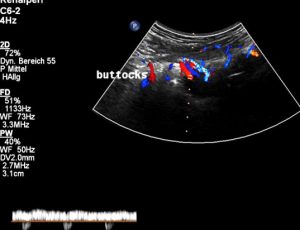

Severely dilated and very painful muscular collateral veins in the left buttock. These veins are part of the collateral network to bypass the obstructed venous segments