- Praktijk-/online-afspraakverdeling

- Vasculaire compressiesyndromen

- Heeft u vragen?

- Checklist vasculaire compressie syndromen

- Musculoskeletale kenmerken van de vrouwelijke puberteit

- Lordosis /Swayback- Oorsprong van vele abdominale compressie syndromen

- Notenkraker-Syndroom is een verkeerde benaming! Lordogenetische linker nieradercompressie is een meer toepasselijke naam!

- May-Thurner-constellatie (May-Thurner-syndroom, Cockett’s syndroom)

- Middellijn (congestie) syndroom

- Bekkenverstoppingssyndroom

- Coeliakie Strandcompressie / Dunbar-syndroom / MALS / Arcuate ligament-syndroom

- Wilkie-Syndroom / Superieur-mescentraal-kwartiersyndroom

- Evlauatie van vasculaire compressies met de PixelFlux-methode

- Pudendale neuralgie bij vasculaire compressiesyndromen

- Migraine en multiple sclerose

- Behandeling van vasculaire compressiesyndromen

- Recent ontdekte vasculaire compressiesyndromen

- Echografie Diagnostiek

- Dienstenpakket

- Functionele kleur Doppler ultrasound – hoe ik het doe

- Perfusiemeting – PixelFlux-methode

- Onderzoek

- Publicaties

- Documenten geschreven door Th. Scholbach

- Eigen publicaties

- Inauguratie van metingen van de weefselpulsatiliteitsindex bij niertransplantaties

- Van notenkraker fenomeen tot middellijn congestie syndroom en de behandeling met aspirine

- Eerste sonografische weefselperfusie meting bij niertransplantaties

- Eerste sonografische tumor perfusie meting en correlatie met tumor oxygenatie

- Eerste sonographische darmwandperfusiemeting bij de ziekte van Crohn

- Eerste sonografische nierweefsel perfuisonmeting

- Eerste sonografische meting van nierperfusieverlies bij diabetes mellitus

- PixelFlux metingen van nierweefsel perfusie

- Publicaties

- Expertise

- Infectie met het Bornavirus

- Wetenschappelijke samenwerking

- Cookiebeleid

- Opmerkingen over medische verklaringen

- Gegevensbescherming

- Cookie Policy (EU)

First description of dynamic compression of the duodenum by the superior mesenteric vein, which becomes congested after eating

A passage disorder in the duodenum can cause serious problems with food intake and the further transport of food. In addition to congenital narrowing of the duodenum, which leads to considerable difficulties with food intake immediately after birth, vascular compression of the duodenum is of particular importance in adulthood.

Vascular compression often develops over a longer period of time due to the displacement of the aorta towards the abdominal wall when the lordosis of the lumbar spine (hollow back) increases and/or the abdominal wall is already flat over the spine, for example because the chest is relatively flat. This situation is often found in patients with soft connective tissue, for example those with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

The duodenum may then be pushed by the aorta against the superior mesenteric artery. The duodenum and the left renal vein run in the angle between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. The clamping of the duodenum therefore often occurs simultaneously with the clamping of the left renal vein, as both compressions are based on the same mechanism.

The compression of the duodenum then makes it increasingly difficult to transport food across the midline, where the aorta and superior mesenteric artery are located. This manifests itself in pain shortly after eating, severe bloating, belching soon after eating and, in severe cases, even vomiting. Patients regularly lose weight because they are unable to consume sufficient food.

Unfortunately, the diagnosis is usually made solely on the basis of a narrow angle between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta. This angle is measured in CT or MR images of the abdomen. As explained elsewhere, this procedure is inadequate and often leads to too many diagnoses.

I am now presenting for the first time a case of vascular compression of the duodenum that is not caused by the superior mesenteric artery but by the superior mesenteric vein (vena mesenterica superior), and only after the patient has eaten.

When the patient was fasting and her stomach was empty, there was no compression of the duodenum. Only the filling of the stomach triggered the compression in the following way:

The patient’s narrow lower thoracic aperture led to very limited space for the upper abdominal organs, which also caused other vascular compressions as a result of increased lordosis in hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

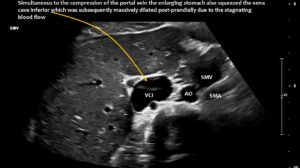

The volume of food ingested and the associated enlargement of the stomach now led to a critical situation: the stomach pushed the hepatic artery (arteria hepatica communis), which runs along the underside of the liver, against the portal vein (vena portae), which carries blood from the spleen and intestines to the liver. This compressed the portal vein and caused blood to accumulate in the splenic vein (Vena lienalis/Vena splenica) and, above all, in the superior mesenteric vein. While the splenic vein runs parallel to the pars horizontalis duodeni, the superior mesenteric vein cuts across the duodenum at a right angle, similar to the superior mesenteric artery. The congestion of the superior mesenteric vein led to compression of the duodenum, even though there was sufficient space between the superior mesenteric artery and the duodenum. However, after food intake, the superior mesenteric artery shifted far to the left and thus no longer formed a clamp with the aorta for the duodenum. The swelling of the superior mesenteric vein, which is supplied with significantly more blood after food intake than when fasting in order to transport food components to the liver, was so severe as a result of the compression of the portal vein that food could no longer pass through the pars horizontalis duodeni. The clinical consequences for the patient were increasing nausea after eating due to the considerable distension of the pars descendens duodeni, rapid satiety, impaired food transport from the stomach despite lively peristaltic contractions of the stomach (misinterpreted elsewhere as gastroparesis), vomiting and significant weight loss. Even feeding via a percutaneous jejunal tube and a gastric tube could not stop the weight loss.

This previously undescribed vascular compression syndrome of the duodenum underscores the need for functional (before and after food intake) and dynamic quantitative colour duplex sonographic examination. This cannot be detected in static images, which are usually taken on an empty stomach (MRI and CT). In barium swallow examinations, which are often used to diagnose superior mesenteric artery syndrome (Wilkie syndrome), the vessels are not imaged and it is not clear what is causing the compression of the duodenum. This means that compression of the portal vein by the enlarging stomach also remains undetected.

Medical history:

The patient, a 21-year-old female, had been suffering from gastrointestinal symptoms since 2018, which became substantially more severe in 2022. She experienced vomiting, pain, nausea, fatigue, bloating and constant exhaustion. Her BMI was 20.08. The daily abdominal pain, which lasted for more than six hours a day, was as severe as 8/10. The pain was located all over the abdomen, but was most pronounced in the left flank, below sternum, on the right side of the navel , and in both lower quadrants.

The upper abdomen protruded after a meal, especially when lying on her back.

Clinical examination:

The patient had a nasogastric tube to reduce stomach pressure but could not use it for feeding due to the above-described severe postprandial abdominal pain, vomiting and nausea. She was therefore nourished via a transcutaneous jejunal tube. Her joints were hyperflexible, giving her a Beighton score of 7/9 , which suggests a hypermobility disorder, likely hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hEDS). Abdominal palpation revealed no pathological lumps, but localised pain was found mainly in the left lower abdomen, the left kidney area, the epigastric angle, and below the left rib cage. Auscultation revealed no vascular bruit and strong peristalsis.

Sonographic findings:

Quantitative and functional colour Doppler ultrasound revealed massive pelvic congestion with reversed flow within the left internal iliac vein; May–Thurner syndrome with severe compression of the left common iliac vein; and fourfold flow acceleration and substantial compression of the vena cava at its passage across the diaphragm. The hepatic veins entered the compressed area of the vena cava. Due to the flat lower thoracic aperture, the superior mesenteric artery was shifted to the left of the aorta.

The left renal vein was severely compressed as it ran in front of the curved origin of the right renal artery, resulting in a flow acceleration to 190 cm/s.

There were signs of mechanical irritation of the celiac plexus block, demonstrated by respiration-dependent movement of the celiac trunk, due to variable pressure from the median arcuate ligament. However, there had not yet been any significant flow acceleration within the coeliac trunk.

There was massive right-sided orthostatic nephroptosis of 12 cm.

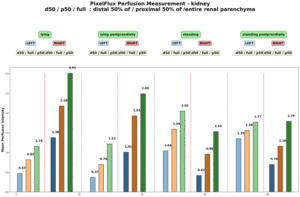

PixelFlux revealed severe suppression of left renal perfusion, while right renal perfusion was heavily influenced by nephroptosis, reducing parenchymal perfusion below that of the left kidney while standing . The main collateral pathway for the compressed left renal vein was a wide auxiliary vein, a tronc réno-rachidien: a complementary vessel that develops in patients with left renal vein compression and drains blood into the spinal canal.

The patient suffered from significant additional orthostatic venous pooling in the pelvis, which reduced left ventricular filling by 67% and circulating flow volume by 63%, explaining the patient’s postural tachycardia.

The superior mesenteric vein appeared normal when the stomach was empty, but showed enormous 5-fold enlargement of its transsectional area after food was consumed. The enlarged vein prevented food from passing across the aorta, as the stomach pushed the superior mesenteric vein against the duodenum, narrowing the passage to such an extent that the descending duodenum enlarged to 38 mm (the usual width is less than 20 mm). The patient reported substantial pain in the area of the distended duodenum, below the right rib cage.

The enlargement of the superior mesenteric vein was due to compression of the root of the portal vein by the common hepatic artery. This resulted in an increasing outflow obstruction from both the distended superior mesenteric vein and the now curled splenic vein.

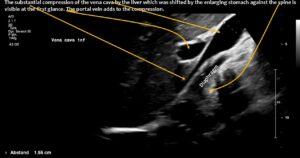

The enlarging stomach shifted the liver against the retrohepatic portion of the vena cava inferior contributing to pain after a meal in the lower abdomen.

Thus, the filling stomach had a quadruple detrimental effect on digestion:

- Due to the limited space restricted by the flat lower thoracic aperture, the volume of food and gas in the stomach after a meal was sufficient to push the liver and its main artery, which runs along the lower surface of the liver, against the root of the portal vein. This produced significant enlargement of the portal vein’s feeding vessels, primarily the superior mesenteric vein.

- Compared to the fasting state, this vein enlarged fivefold and formed an abutment for the aorta, both of which squeezed the horizontal portion of the duodenum and obstructed the passage of food. This caused postprandial nausea and vomiting, as well as an inability to be fed via a nasogastric tube.

- The postprandial increase in blood flow towards the small bowel and the subsequent increase in venous return into the superior mesenteric vein certainly contributed to the stiffness of the vein, which made compression of the duodenum even more effective.

- Pressing the liver against the vena cava inferior creating an additional pain in the right lower abdomen after a meal.

To the best of my knowledge, this mechanism has not yet been described in the medical literature. This underscores the necessity of taking into account all possible factors contributing to compression of an abdominal organ.

- Flattening the abdominal cavity in patients with a shallow lower thoracic aperture, which is a hallmark of patients with connective tissue disorders.

- Increased lumbar lordosis, which presses the abdomen against the abdominal wall or rib cage.

- The sometimes unexpected effect of the additional volume required by normal amounts of food or postprandial intestinal gas production.

- Increased blood flow volumes distend blood vessels as a physiological effect of mechanisms such as ingestion, which was relevant in this case, but muscle work or increased brain activity in other patients and other vascular territories .

- Dynamic compression of blood vessels has remote effects on vascular territories, increasing collateral pathway volumes or, as in this patient, increasing congested vein volumes.

- The effect of certain body postures on the distribution of intra-abdominal compartments.

- The effect of breathing on the volume of the abdominal cavity, which alters the space available for structures passing across the diaphragm.

Such a complex situation involving multiple anatomical and functional peculiarities cannot be fully understood using conventional CT or MRI scans, or any other gastrointestinal tests. It requires a quantitative and functional colour Doppler sonographic examination using the PixelFlux technique.

Excerpt from the functional imaging:

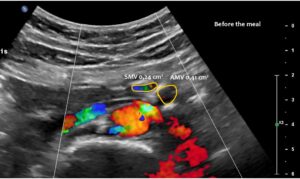

Normal size of the superior mesenteric vein which is slightly slimmer than the superior mesenteric artery as long as the patient was fasting. However, due to the limited space in the flat upper abdomen the superior mesenteric artery already is shifted to the left side of the aorta instead of lying precisely in front of it.

Here, the unique mechanism causing compression of the duodenum by the enlarged superior mesenteric vein is demonstrated. In contrast to conventional SMA syndrome, the superior mesenteric vein acts as a pillar against which the aorta presses, thus obstructing the duodenum. It is important to be aware of the variability in the position of the superior mesenteric artery in patients with a flat abdominal cavity. When the stomach is full, it may shift further to the left (or right) of the SMA than in the fasting position.

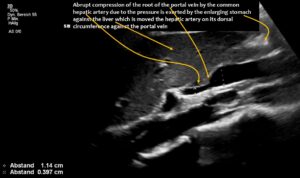

The longitudinal section showing the continuation of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) into the root of the portal vein reveals an abrupt narrowing of the portal vein, caused by compression from the common hepatic artery.

Enlargement of the superior mesenteric vein can be observed as early as five minutes after eating, progressing to fivefold enlargement of the transsectional area after seven minutes.

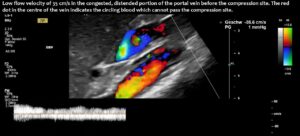

Compression of the superior mesenteric vein and its distension not only compresses the duodenum, but also reduces venous return from the small bowel, which can impair food absorption. Blocked blood flow at the compression site can be demonstrated by a whirling blood stream in front of the compression. Subsequent layers demonstrate antegrade and retrograde flow, as can be seen in the layering of blue and red flow inside the enlarged vein, pointing to changing flow directions and the different flow directions in these layers as highlighted by the spectral analyses at the bottom of the image.

Postprandial compression of the vena cava contributed to eating difficulties due to pain caused by obstructed venous return from the abdomen to the heart.

Pixel flux measurements of renal perfusion demonstrate the severe impact of compression of the left renal vein, resulting in pain below the left rib cage. This pain increases after meals due to interaction between the duodenum and the left renal vein, both of which pass between the aorta and superior mesenteric vessels.